Moneyball is the award-winning book by Michael Lewis revealing how a low budget team (the Oakland A’s) was able to field winning teams despite competing with clubs much larger budgets. The sub-title of the book – The Art of Winning an Unfair Game – is especially apt in today’s big money collegiate sports landscape.

The conventional wisdom is that big budget schools will have a massive financial advantage in the upcoming revenue sharing era. A $ 20 million revenue sharing commitment represents only a 10% increase in costs to a school with a $200 million-dollar annual athletic budget, while this same commitment would represent a 40% increase in annual costs to a school with a $ 50 million budget – 4 times as much in relative terms. For a smaller budget school this would represent an unaffordable and financially reckless expenditure of funds … or would it?

For a few smaller schools I believe there may be rationale to commit to this increase, and I’m willing to bet at least one will. And this might keep some big school athletic directors up at night, because similar to the premise in Moneyball, an upstart school is going to seriously challenge the traditional cost structure of big-time athletic departments.

College presidents often state that athletics are the “front porch” of a university … it’s not the most important room in the house, but it’s the most visible. Televised football is in part a 3-hour infomercial for schools with scenes of campuses and students, as well as airtime allocated for schools to highlight their academic and research programs. Televised sports keep alumni and boosters engaged, and are a very effective tool for schools to recruit applicants nationwide. College athletics generate significant returns that benefit the school financially, and this is one of the primary reasons many schools make significant investments in athletics.

A landmark study by Doug Chung of Harvard University determined that athletic success has a significant impact on a school’s enrollment demand. In a study titled “the Flutie Effect”, Chung determined that schools that went from mediocre to great on the football field saw applications increase by almost 18% One of his conclusions was that athletic success has a significant long-term goodwill effect on future applications as well as the quality of the applicants.

The University of Alabama hired Nick Saban as head football coach in 2007. Subsequently, the Crimson Tide won 6 National Championships, and its enrollment statistics were also widely successful. From 2006 to 2020, Alabama’s first year undergraduate enrollment increased by 49% – over 6 times the average increase for 4-year public schools during the same period.

The percentage of Alabama’s out of state undergraduate enrollment increased even more dramatically. In 2006 out of state students represented 33% of Alabama’s undergraduate enrollment while 67% were in-state residents. In 2021 these percentages had essentially flipped: 58% of the undergraduate enrollment was out of state while only 42% were Alabama residents. This is a major financial boom for the school, as out-of-state tuition at a 4-year public school is typically about 3 times higher than in-state tuition.

Schools with FBS (top level) football programs increased their non-resident student enrollment at a much greater percentage than schools without FBS football programs. The University of Oregon is another school with a very successful athletics program. In 2006, Oregon’s first year undergraduate enrollment was 68% in-state and 32% out of state. In 2021 the school’s first year enrollment was majority out of state (51%) while Oregon residents (49%) were less than half.

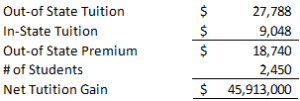

An interesting example of the Flutie Effect is Boise State University. After a riveting Fiesta Bowl win over Oklahoma in 2007, the school saw a 40% spike in freshmen applications. In 2006 Boise State’s first year undergrad enrollment was 85% in state and 15% out of state. After the Fiesta Bowl win put Boise State “on the map” non-resident enrollment has steadily increased, and in 2021 a majority of the school’s first-year undergraduate students (52%) came from outside of Idaho – a 250% increase in non-resident enrollment. The school’s finances are positively impacted by this development since annual tuition for out of state students is $ 27,788 – three times the $ 9,048 tuition for Idaho residents.

During the 15-year 2006-20 period Boise State had tremendous success on the football field: a winning percentage of 83% (161-32). Now compare this to the state’s namesake school – the University of Idaho. During the same 15-year period, Idaho’s football team won only 31% of their games (54-121) and actually moved down a sub-division from FBS to FCS. Idaho is an excellent school, and while its total enrollment has been steadily increasing, its percentage of out of state students has remained flat while Boise State’s increased 250% over the same period. There are other factors, but athletic success appears to have clearly played a significant role. Boise State’s highly visible football program has marketed the school to hundreds of thousands potential applicants nationwide, while Idaho’s has not.

Boise State currently has a total full-time undergraduate enrollment of around 14,000. This includes around 3,100 non-resident undergrads likely attributable to the Flutie Effect realized since the 2007 Fiesta Bowl. After adjusting for the school’s 79% retention rate, the result is a net gain of around 2,450 ongoing non-resident undergrad students. This results in an annual tuition gain of almost $ 46 million:

The actual net tuition gain is reduced by scholarships, financial assistance and other discounts, but in-state tuition is also reduced by these items, so the net gain from out of state students remains very significant. Boise State’s success on the football field also results in additional financial benefits from higher game day attendance, booster and sponsor support, and bowl game revenues.

In a time when US college enrollment is declining, many schools are facing a crisis, and a chance to enhance their future viability by realizing a Flutie effect is not lost on many college heads. But cases like Boise State are the exception. Historically, if you were a smaller school you realistically could not compete on the national stage with schools with $ 200 million budgets, highly paid coaching staffs, stadiums that seat 100,000 fans and national championship pedigrees. But revenue sharing may change this to a degree, which is why there will likely be a Moneyball upstart.

For the 12-team College Football Playoff (CFP) there are a maximum of 11 spots available for the current 68 power conference schools, which also means 57 will not make the cut. At least one CFP spot is guaranteed to a Group of Five (G5) school – the other 68 FBS schools such as Boise State not in a Power 4 Conference. The odds of 68:1 don’t seem very promising, but this is where it gets interesting. Similar to the joke about the two hikers and the angry bear, a G5 school doesn’t need to outrun a P4 school, it only needs to outrun its G5 competitors. And revenue sharing may change these odds dramatically.

While virtually all P4 schools will likely opt in to a $ 20.5 million revenue sharing commitment, G5 schools will only be paying a fraction of this, likely around $ 3 million per year on average. So, a G5 school committing to a maximum revenue sharing commitment would have a war chest 6 to 7 times that of its competitors … a massive recruiting advantage. This could quickly lead to success on the football field, likely the odds-on favorite to win its conference and an enhanced chance for a spot in either the CFP or a high-profile Bowl game, both of which would bring the school a big splash of national visibility.

And a G5 school offering recruits revenue sharing of 6 to 7 times its conference competitors is also going to have an enhanced chance of making the NCAA men’s and women’s basketball tournaments, as well as post-season appearances in other sports, all of which would market that school to potential applicants nationwide.

Bolstering school enrollment is critical to survive, and opting to pay $20 in million revenue sharing – while definitely risky – could be a very well thought out strategy for the right school if the return on investment might be national exposure, increased enrollment, enhanced booster support and $ 40 or $ 50 million in additional revenue. And the school may not even need to use its own money to make the investment, a wealthy alum or group of boosters could make contributions designated to fund a revenue sharing moonshot. For these reasons I believe at least one school will pursue a Moneyball type approach:

We don’t need a $ 200 million budget, we don’t need to pay coaches $ 10 million per year, we don’t even need Bill Belichick. We only need to pay our athletes $ 20 million per year.

A G5 school successfully pursuing this mantra could make some big school administrators very uneasy. If it all comes down to essentially how much we pay our athletes, why do we need all these other costs?

Questions on our data? Contact us at: NIL-NCAA.com

Statistics compiled & edited by Patrick O’Rourke, CPA Washington, DC ![]()